The old adage says ’tis better to give than to receive. Christian Europeans must think so, we currently dominate the “giving” market to near monopoly. Some of us, though, are just a little reluctant to admit that our premier  holiday, with its message of peace on earth, good will toward men, could really induce paroxysms of agonised torment and loathing unseen since Hammer Films introduced Dracula to the crucifix. This year, Scrooge Inc. is urging people to “do the right thing” and refrain from sending Christmas cards — to save the planet. What cards do survive are purged of Christian iconography, and come out of the cultural autoclave piping hot and pasteurised to a cloying oiliness usually confined to cheese spread. Our nativity scenes and carolling, so excruciatingly painful, have been replaced by a lavish smorgasbord of op-ed items reminding us that the real blessing of the season is exposure to a panoply of cultures and celebrations innately superior to our own.

holiday, with its message of peace on earth, good will toward men, could really induce paroxysms of agonised torment and loathing unseen since Hammer Films introduced Dracula to the crucifix. This year, Scrooge Inc. is urging people to “do the right thing” and refrain from sending Christmas cards — to save the planet. What cards do survive are purged of Christian iconography, and come out of the cultural autoclave piping hot and pasteurised to a cloying oiliness usually confined to cheese spread. Our nativity scenes and carolling, so excruciatingly painful, have been replaced by a lavish smorgasbord of op-ed items reminding us that the real blessing of the season is exposure to a panoply of cultures and celebrations innately superior to our own.

Canada boasts the fastest growing Jewish community outside Israel, a mushrooming North American Muslim population expected to eclipse Jewish numbers by the millennium, and the largest (Halifax) non-Asian Buddhist community in the world. You may be tempted to ask, “What’s the church doing?”. Several ecumenical groups are sponsoring flagellant pilgrims on a tour of the Middle East to apologise for the Crusades. If they happen to be grovelling near the seat of all Christendom, let them gaze in silent awe at Bethlehem’s Manger Square — now an asphalt surfaced parking lot.

Shall we hang the holly, or each other? Christmas is difficult to defend, because however much we may love our traditions, the church has really only abandoned its centuries-long persecution of “pagan” heretics in order to cannibalise itself.. According to the Population Reference Bureau, there are 2 billion persons in the world under the age of 18. Of these, 85 per cent are Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist or Jewish. Thus, at an excessively generous estimate, a mere 378 million humans (no indication what portion are European) may or may not perpetuate our belief system. The message is the same as ever: we cannot defend what we do not know.  At the dawn of history Europe was a dark forest. For men and women rooted in, and wholly dependent upon nature’s provender, the ever darker and colder days must have made this a season of terrors.

At the dawn of history Europe was a dark forest. For men and women rooted in, and wholly dependent upon nature’s provender, the ever darker and colder days must have made this a season of terrors.

Deepening winter meant food shortages as vegetation  succumbed to the cold and shortened days restricted the hunt. Later pastoralists would be compelled to slaughter some of their valuable animals as pastures were smothered under snow. What likely began as an act of sheer desperation (propitiation rites to coax back the waning life-giver) were formalized when one of history’s nameless geniuses realised that the course of the sun could be not only be plotted, but the day of it’s return accurately predicted. Europe’s monolithic standing stones and observatories bear silent witness to the power these ideas had for our forebears. More remarkably durable, is the cultural persistence of this legacy. For all their celebrated differences, pre-Christian Yule and our Christmas are more like than unlike; from themes of hope and redemption to external trappings, the two are clearly kindred feasts.

succumbed to the cold and shortened days restricted the hunt. Later pastoralists would be compelled to slaughter some of their valuable animals as pastures were smothered under snow. What likely began as an act of sheer desperation (propitiation rites to coax back the waning life-giver) were formalized when one of history’s nameless geniuses realised that the course of the sun could be not only be plotted, but the day of it’s return accurately predicted. Europe’s monolithic standing stones and observatories bear silent witness to the power these ideas had for our forebears. More remarkably durable, is the cultural persistence of this legacy. For all their celebrated differences, pre-Christian Yule and our Christmas are more like than unlike; from themes of hope and redemption to external trappings, the two are clearly kindred feasts.  The word Yule comes from the Norse Jul, meaning wheel. The ancient Europeans saw time as a cyclic, as opposed to a linear event. You can see that in merely marking equinox and solstice, their (apparently) “controversial” sun wheel formed the foundations for both swastika and the (apparently) “objectionable” Celtic cross. One of the recurrent themes in Sir James Frazer’s seminal study of mythology, The

The word Yule comes from the Norse Jul, meaning wheel. The ancient Europeans saw time as a cyclic, as opposed to a linear event. You can see that in merely marking equinox and solstice, their (apparently) “controversial” sun wheel formed the foundations for both swastika and the (apparently) “objectionable” Celtic cross. One of the recurrent themes in Sir James Frazer’s seminal study of mythology, The  Golden Bough, was the ritual slaying of the old king by the new. Since his great book was originally published 1890, perhaps we can be generous (just this once) and forgive the now unforgivable terminology. Frazer named the oak the “pre-eminently sacred tree of the Aryans … its worship is attested for all the great branches of the Aryan stock in Europe.” (Macmillan, 1963 p. 870). The point is that Yule represented the rebirth of the Oak King, as much as that of the sun. Solstice was the occasion for the young Oak King (summer) to slay the ageing Holly King (winter). Yule blended elements of both Christmas and the New Year. Taking stock of the previous year, swearing oaths, and making resolutions would have been as familiar to our European forefathers as the image of the aged old year being unceremoniously hustled off stage to make way for the New Year’s baby.

Golden Bough, was the ritual slaying of the old king by the new. Since his great book was originally published 1890, perhaps we can be generous (just this once) and forgive the now unforgivable terminology. Frazer named the oak the “pre-eminently sacred tree of the Aryans … its worship is attested for all the great branches of the Aryan stock in Europe.” (Macmillan, 1963 p. 870). The point is that Yule represented the rebirth of the Oak King, as much as that of the sun. Solstice was the occasion for the young Oak King (summer) to slay the ageing Holly King (winter). Yule blended elements of both Christmas and the New Year. Taking stock of the previous year, swearing oaths, and making resolutions would have been as familiar to our European forefathers as the image of the aged old year being unceremoniously hustled off stage to make way for the New Year’s baby.

Celts, Norse and Teutons considered trees the earthly representatives of the gods. Sacrificing a Yule log to the  dying sun was a universal practice. Local customs varied from the enormous tree brought into the Scandinavian home, to the “heavy block of oak fitted into the floor of the hearth, where, though it glowed under the fire, it was hardly reduced to ashes within a year … in the valleys of the Sieg and Lahn” (Frazer, p. 834). The Yule log was decorated with evergreens and ribbons, and a libation poured over it before the lighting. The magical properties attributed to the sacred oak can hardly be over-emphasized. Each year a brand was rescued from the flames and reserved to rekindle next year’s Yule log. During the interim, it served as a talisman to protect the home from a variety of evils, including lightning. The ashes were carefully swept from the grate and saved to impart a magical efficacy to a variety of nostrums.

dying sun was a universal practice. Local customs varied from the enormous tree brought into the Scandinavian home, to the “heavy block of oak fitted into the floor of the hearth, where, though it glowed under the fire, it was hardly reduced to ashes within a year … in the valleys of the Sieg and Lahn” (Frazer, p. 834). The Yule log was decorated with evergreens and ribbons, and a libation poured over it before the lighting. The magical properties attributed to the sacred oak can hardly be over-emphasized. Each year a brand was rescued from the flames and reserved to rekindle next year’s Yule log. During the interim, it served as a talisman to protect the home from a variety of evils, including lightning. The ashes were carefully swept from the grate and saved to impart a magical efficacy to a variety of nostrums.  Holly and mistletoe were venerable plants because (as evergreens do) they remained steadfast to triumph over the cold. Moreover, they were powerful enough to fruit in a bleak and barren season. Holly is still affixed to the door of our houses without our quite understanding why.

Holly and mistletoe were venerable plants because (as evergreens do) they remained steadfast to triumph over the cold. Moreover, they were powerful enough to fruit in a bleak and barren season. Holly is still affixed to the door of our houses without our quite understanding why.

It was assumed that the “points” would snag the evil-intentioned and prevent their entering. When holly was brought into the house, it became an object of lively interest and speculation. It was (incorrectly) believed that the very sharp “pointed” leaves were male, the smoother, female. Thus, the type of holly determined who should “rule the roost” in the coming year. Victorian merchant, Henry Mayhew estimated that London merchants sold 250,000 bushels during the 1851 Christmas (not to imply there was a lively trade in alternately pointed and smooth leaves).

Mistletoe has better retained vestiges both of the folk lore and high honours once accorded to it.  Long called Allheal, the word “mistletoe” comes to us from the Norse. Where the oak was a powerful symbol of God, mistletoe was regarded as having the same dependent relationship to the oak as man’s to heaven. Sacred to both Norse and Celt, this remarkable little plant (the golden bough of Frazer’s title) has survived Christianization more successfully than most, even to adorning the alter at York Cathedral on Christmas Eve, from which widespread amnesties were announced. Among pre-Christianized Germans, mistletoe served to exorcise ghosts from houses. At this time of year, using a golden sickle and making certain none fell to the ground, the Druids cut mistletoe branches from a sacred oak, and distributed bunches to each family under their care. Our kissing tradition was known to the Romans, but even this likely hearkens back to mistletoe’s long association with fertility. Infusions were given both to barren women and to those in labour, to relax childbearing muscles. One of the curious features of ancient rites was the wassailing of the trees. Here, the men of the village went out to

Long called Allheal, the word “mistletoe” comes to us from the Norse. Where the oak was a powerful symbol of God, mistletoe was regarded as having the same dependent relationship to the oak as man’s to heaven. Sacred to both Norse and Celt, this remarkable little plant (the golden bough of Frazer’s title) has survived Christianization more successfully than most, even to adorning the alter at York Cathedral on Christmas Eve, from which widespread amnesties were announced. Among pre-Christianized Germans, mistletoe served to exorcise ghosts from houses. At this time of year, using a golden sickle and making certain none fell to the ground, the Druids cut mistletoe branches from a sacred oak, and distributed bunches to each family under their care. Our kissing tradition was known to the Romans, but even this likely hearkens back to mistletoe’s long association with fertility. Infusions were given both to barren women and to those in labour, to relax childbearing muscles. One of the curious features of ancient rites was the wassailing of the trees. Here, the men of the village went out to  the orchards carrying the wassail bowl, to alternately serenade and browbeat the apple trees.

the orchards carrying the wassail bowl, to alternately serenade and browbeat the apple trees.

There were songs, dances and libations (for tree and man) until finally, in frustration, the trees would be threatened with the axe if they did not produce well in the coming year. (A temptation not entirely unknown to modern gardeners). A newspaper account of 1851 documents Devonshire men firing guns (charged only with powder) at the trees. And yet, far from England, Romanians enacted a virtually identical rite. As the housewife kneaded a special holiday dough in the kitchen, her husband would pass through the house on his way to the orchard, in a vile temper. She followed anxiously behind as he passed from tree to tree, threatening to cut down each barren one. She would urge him to especially spare this one or that, saying: “Oh no, I’m sure this tree will be as heavy with fruit next year as my hands are with dough this day.”  Most of the things we love about Christmas are old beyond reckoning.

Most of the things we love about Christmas are old beyond reckoning.

The radiant light and warmth of our homes, the good cheer, generosity and hospitality all predate Christianity, and are just as likely to outlive oily commercialism. The strands, ribbons and garlands tethering our Christmas observances to older beliefs are an inextricably tangled lot. The Encyclopaedia Britannica says: “The traditional customs connected with Christmas have developed from several sources as a result of the coincidence of the birth of Christ with the pagan agricultural and solar observances at midwinter.” (15th edition, 1985, “Christmas”) But the date assigned to Christ’s birth is no coincidence. The first reference to the date does not occur until 354 A.D., in a Roman almanac. By then the church had apparently conceded that, as with Samhain, converts would bring their beloved customs with them, and efforts to discredit or dislodge these would merely prove futile. Thus in the fourth-century, the first Christian Emperor, Constantine, assigned Christ’s nativity to December 25. Strangely unfamiliar to us, and real testimony to the power of historical censorship, are uncanny parallels between Christian doctrine and the great solstice/Roman feast of dies natalis solis invicti (birth of the invincible sun). It is  not known whether Mithraic practice was imported from Iran (possibly as a conduit from Indo-European tribes further east) or, as the Congress of Mithraic studies suggested in 1971, it was an entirely new mystery religion, merely borrowing the name “Mithras”.

not known whether Mithraic practice was imported from Iran (possibly as a conduit from Indo-European tribes further east) or, as the Congress of Mithraic studies suggested in 1971, it was an entirely new mystery religion, merely borrowing the name “Mithras”.

The cult arose in the Mediterranean world and shared the stage for a time with Christianity, although Mithraism was by far the more successful of the two. It was the predominant form of worship among Roman men of all classes, from emperor to slave. With it’s emphasis on high standards of behaviour; temperance, self-control and compassion — even in victory, it established a code of behaviour congenial to fighting men. It’s curious that we are largely ignorant of this religion which in so many particulars, seems to have anticipated Christianity.

To save erring humanity from sin, Mithras (the Invincible Sun) was born into the world to offer adherents salvation. He was born (dies natalis solis invicti) in a cave, of a virgin mother on December 25 — a date established well in advance of the Christian era. In his fourth-century revisions, the emperor Constantine also “moved” Christian worship from Saturday to Sunday, the “venerable day of the sun” of Mithraic devotions.

There is evidence of Mithraic practice from 1,400 B.C. Again like Christ, Mithras at his death, ascended to heaven. Although in this case, it was to wield the sun chariot and act as intermediary messenger between man and the good god of airy light. Even as the Christian church expanded, it remained impotent in the face of ingrained habits of feasting and pagan  merriment; so these were routinely “purified”, “consecrated” to Christ, and assigned a higher purpose. In time, the neglected old gods may have disappeared, but their legacy is decidedly with us to this day. Most of our Christmas traditions were well established by the Middle Ages, when miracle plays relied upon a single piece of scenery; the decorated “paradise” tree. This is the most likely progenitor of our Christmas tree. A

merriment; so these were routinely “purified”, “consecrated” to Christ, and assigned a higher purpose. In time, the neglected old gods may have disappeared, but their legacy is decidedly with us to this day. Most of our Christmas traditions were well established by the Middle Ages, when miracle plays relied upon a single piece of scenery; the decorated “paradise” tree. This is the most likely progenitor of our Christmas tree. A  more fanciful source describes St. Boniface’s 8th century efforts to convert the heathen German. Happening across a group of idolaters near a venerable old oak, he felled their sacred tree in a rage. As he did so, a small fir tree sprang forth. The convenient miracle (and shape of the tree) served rather nicely for a first lesson on the nature of the Trinity.

more fanciful source describes St. Boniface’s 8th century efforts to convert the heathen German. Happening across a group of idolaters near a venerable old oak, he felled their sacred tree in a rage. As he did so, a small fir tree sprang forth. The convenient miracle (and shape of the tree) served rather nicely for a first lesson on the nature of the Trinity.

That region, Thuringia, was to become the cradle of an enormous Christmas decorations industry. A Christmas tree in the German home was a relative commonplace by the 16th century. Martin Luther is credited with illuminating more than the Protestant world. Amazed at the brilliance of stars twinkling through fir boughs, he attached candles to the family tree when he arrived home in an effort to replicate the effect for his children. From Tannenbaum to tinsel (of real silver, invented in 1610), no country has taken Christmas to heart as Germany has, and no country has contributed to the Christmas canon with the same infallible charm and genius.

In 1841, Prince Albert and Queen Victoria’s enthusiasm for their Christmas tree gentrified what had up ’til then, been regarded as a peculiar German eccentricity. And the British ran with it. Two years later Charles Dickens’ Christmas Carol appeared for the first time. The first Canadian Christmas tree was introduced by yet another German, General Von Reidesel, at Sorel, Quebec in 1781. Christmas, King of Feasts, has enjoyed a long and uninterrupted reign in Canada; from the founding of the colony of New France, to this day when — suddenly — all things remotely Christian are either sneered at or simply too painful to endure. The suppression of Christmas is hardly a new phenomenon. It has often been controversial to the point of prohibition. A great favourite of the Middle Ages was the Christmas Eve Festival of the Ass, when a young girl with a babe in arms rode a donkey into the church. Throughout the mass, prayers ended with a braying hee-haw from priest and congregation alike. When the church tried to proscribe the practice in the 15th century, it  discovered to its horror that parishioners were inordinately attached to the blasphemous liturgy which persisted over many embarrassing years. From the 11th to 17th centuries, Christmas was England’s great festival.

discovered to its horror that parishioners were inordinately attached to the blasphemous liturgy which persisted over many embarrassing years. From the 11th to 17th centuries, Christmas was England’s great festival.

Records from 1252 show that Henry III had 600 oxen roasted for the feasting. Yet, even then, fundamentalists were objecting that Christmas was essentially a heathen solstice festival, only brushed with the thinnest Christian veneer. Worse, it was quite clearly a popish Christian veneer. In 1562 John Knox outlawed the feast in Scotland, and under the cold gaze of Oliver Cromwell, the English Parliament hastened to follow suit in 1644. When the House of Commons sat on Christmas day, sheriffs were sent out to ensure businesses remained open. Pro-Christmas and anti-Christmas factions rioted in the streets. Thus, when Puritans, Quakers, Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists, Mennonites and other “plain folk” emigrated to America, they arrived with their distaste for the holiday intact. In 1706, a Boston mob smashed windows in a church holding “heathen” Christmas services.  The term “Xmas” is not an affront. X is the first letter of the Greek word for Christ (Xristos). Early Christians understood that this meant “Christ’s mass” in Greek.

The term “Xmas” is not an affront. X is the first letter of the Greek word for Christ (Xristos). Early Christians understood that this meant “Christ’s mass” in Greek.

But once people were no longer educated in the classical mode, the term took on a sinister aspect and people were (and remain) convinced that this was a deliberate smear.For once, it isn’t. Boxing Day has nothing to do with returning gifts. St. Stephen’s Day (December 26) was the traditional day to empty and distribute alms from church poor boxes. Unknown in the U.S., Boxing Day is called Kwanzaa.  Another German invention, the advent calendar dates back to at least 1851. Beginning December 1st, excited children open a little door to a poem and treat every day, right up to Christmas Eve. The twelve days of Christmas begin on Christmas Eve and end on Epiphany, January 6. This idea, like so many others, predates Christianity. Christmas Eve was considered by many Europeans to be a Night of Miracles.

Another German invention, the advent calendar dates back to at least 1851. Beginning December 1st, excited children open a little door to a poem and treat every day, right up to Christmas Eve. The twelve days of Christmas begin on Christmas Eve and end on Epiphany, January 6. This idea, like so many others, predates Christianity. Christmas Eve was considered by many Europeans to be a Night of Miracles.

At the stroke of midnight, farm animals were said to kneel and worship the miracle of His birth. In a more cynical version, these same animals acquire the gift of speech and promptly exchange gossip about their masters (eavesdropping led to being struck  dumb). German Christmas Eve services introduced the charming custom of cradle rocking. To emphasize the Christ child’s humanity, the alter boys would enter the precincts of the manger scene, and rock the cradle as they sang lullabies to the infant.

dumb). German Christmas Eve services introduced the charming custom of cradle rocking. To emphasize the Christ child’s humanity, the alter boys would enter the precincts of the manger scene, and rock the cradle as they sang lullabies to the infant.

After church, while anxious German children wait in an ecstasy of torment, their parents lay out the gifts, decorate and light the tree. When the doors are opened and the shimmering confection is gasped over (with pails of water standing by) the presents are opened. A tradition unique to France and Canada is Reveillon, the meal following Christmas Eve church service. Originally a simple snack, in the Christmas way, it has ballooned into an elaborately lavish full course dinner. Common in English Canada from the late 1800s, it was relatively unknown in rural Quebec before the 1930s.

C reches seem to be a source of special anguish to the sensitivity patrol. One suspects that North America’s church foundations are kept in plumb with the sheer weight of Marys, Josephs, infants, kings, shepherds and animals permanently exiled to the basement. What we do have, to excess, are resentful dogs in the manger. In the U.S., there are creche-bylaws: one giant candy cane and Frosty the snowman stuffed into a nativity scene may or may not be enough to mitigate the (apparently) intolerable presence of the Christ child.

reches seem to be a source of special anguish to the sensitivity patrol. One suspects that North America’s church foundations are kept in plumb with the sheer weight of Marys, Josephs, infants, kings, shepherds and animals permanently exiled to the basement. What we do have, to excess, are resentful dogs in the manger. In the U.S., there are creche-bylaws: one giant candy cane and Frosty the snowman stuffed into a nativity scene may or may not be enough to mitigate the (apparently) intolerable presence of the Christ child.

And there’s the disclaimer option: a visible notice must state that “this creche is privately sponsored by so-and-so”. Without constitutional guarantees, the Canadian creche has simply vanished. The notable exception is Riviere Eternite, in the Saguenay Lac Saint Jean region, north of Quebec City. Here, the enthusiast can revel in several hundred creche displays of every possible description from mid-November to mid-January . The creche in Canada dates back to the beginning of the colony. The Ursuline nuns made bee’s wax images of the baby Jesus, wreathed in children’s hair, from the time the order first appeared in the New World. Creches have disappeared relatively recently, once again, succumbing to “pouting power” and the forces of political correctitude.

Raising our voices to sing traditional carols extolling the virtues of peace and good will is, apparently, yet another deliberate affront, and a provocation which can no longer be endured. The irony in this bit of reverse-tolerance is that Canada’s first Christmas carol, Jesous Ahatonhia, (Jesus is Born) was penned at unimaginable expense. It was written in the Huron language by the Jesuit, Saint Jean de Brebeuf in the early 1600s. A descendent of William the Conqueror and St. Louis of France, Brebeuf arrived in Canada with Samuel de Champlain’s 1625 expedition. Far from the typecast missionary bully, Brebeuf appears to have been a thoughtful and intelligent man, as evidenced in his dispatches to the Jesuit Relations.

Raising our voices to sing traditional carols extolling the virtues of peace and good will is, apparently, yet another deliberate affront, and a provocation which can no longer be endured. The irony in this bit of reverse-tolerance is that Canada’s first Christmas carol, Jesous Ahatonhia, (Jesus is Born) was penned at unimaginable expense. It was written in the Huron language by the Jesuit, Saint Jean de Brebeuf in the early 1600s. A descendent of William the Conqueror and St. Louis of France, Brebeuf arrived in Canada with Samuel de Champlain’s 1625 expedition. Far from the typecast missionary bully, Brebeuf appears to have been a thoughtful and intelligent man, as evidenced in his dispatches to the Jesuit Relations.

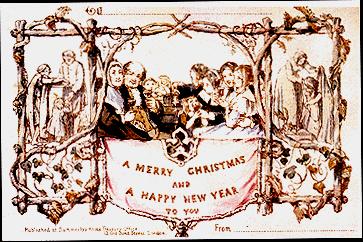

In 1649, Brebeuf and Gabriel Lalement were taken prisoner by the Iroquois and tortured to death. Their martyrdoms are considered among the most horrific in Christian history. Brebeuf’s feast day is September 26.  On July 9, 1998, the New York Times ran an article entitled “Will the World Buy Santa’s Turkish Heritage?” As this very old card illustrates, the world has seen kindly old semitic gentlemen before. Like everyone else, Europeans simply prefer that their kindly old gentlemen resemble their own grandfathers. Born in 280 A.D., St. Nicholas was Bishop of Myra, (then part of the Holy Roman Empire) — now Demre, in Islamic Turkey. Given the population shifts in this region, it’s doubtful whether “Santa” was semitic at all. But since the very idea undermines our “claim” to Christmas; brace yourself for more speculation. Early illustrations certainly show a St. Nicholas of European mien. During a period of famine, he established his r

On July 9, 1998, the New York Times ran an article entitled “Will the World Buy Santa’s Turkish Heritage?” As this very old card illustrates, the world has seen kindly old semitic gentlemen before. Like everyone else, Europeans simply prefer that their kindly old gentlemen resemble their own grandfathers. Born in 280 A.D., St. Nicholas was Bishop of Myra, (then part of the Holy Roman Empire) — now Demre, in Islamic Turkey. Given the population shifts in this region, it’s doubtful whether “Santa” was semitic at all. But since the very idea undermines our “claim” to Christmas; brace yourself for more speculation. Early illustrations certainly show a St. Nicholas of European mien. During a period of famine, he established his r eputation in restoring life to three brothers who were butchered, salted, and ready for consumption. In another exploit, his anonymous gifts rescue three sisters from a pending life of prostitution. St. Nicholas’ real world was hardly the cozy North Pole confection he inhabits today. Protector of sailors, he was among the first arrivals to the New World. Columbus named a bay after him in 1492. The idea of the kindly old gift giver was so firmly fixed in the European mind, that even Luther’s Reformation was powerless against this saint. Over centuries, Santa Claus has been subject to constant revision, and not a little propaganda.

eputation in restoring life to three brothers who were butchered, salted, and ready for consumption. In another exploit, his anonymous gifts rescue three sisters from a pending life of prostitution. St. Nicholas’ real world was hardly the cozy North Pole confection he inhabits today. Protector of sailors, he was among the first arrivals to the New World. Columbus named a bay after him in 1492. The idea of the kindly old gift giver was so firmly fixed in the European mind, that even Luther’s Reformation was powerless against this saint. Over centuries, Santa Claus has been subject to constant revision, and not a little propaganda.

During the War between the States, when President Lincoln asked Thomas Nast for a patriotic Christmas picture, Nast obliged. Some historians say that for Southerners caught up in a vicious, demoralising war, one of the most demoralising moments of all was in seeing Santa consorting with Yankees. The Santa Claus we know, is a homogenised concoction of several European traditions, crystallised by Clement Moore’s poem (A Visit From St. Nicholas), Thomas Nast’s illustrations for Harper’s Weekly, and of course, Haddon Sundblom’s 1931-1964 illustrations for Coca-Cola.  Now that you’ve read this far, here’s your Christmas present.

Now that you’ve read this far, here’s your Christmas present.

An interesting article in the November 13, 1998 Toronto Star notes this year’s record breaking attendance at Remembrance Day services and the increase in poppy sales. Columnist Richard Gwyn says “Remembrance Day has become a kind of tribal day of celebration for English Canadians”. We may (mistakenly) believe that here, at last, is an unassailable holiday. Surely no one would object to the solemn recognition of our war dead — if we’re not too “Christian” about it? Not so. Sikh and Jewish organizations attempted to discourage people buying poppies from Legion branches upholding the headgear ban in 1994, albeit without much success. Mr. Gwyn’s intriguing “tribal” theory doesn’t go far enough.

A renewed interest in Remembrance Day hardly accounts for Hallowe’en’s growing popularity, any more than it explains the inordinately early appearance of Christmas decorations (on private property) this year. Bullied, browbeaten and badgered Canadians are drawing the line, ignoring the thousand hints, refusing to scorn our traditions on demand, and thumbing our collective noses at the sensitivity patrol. In the time honoured way of resistance, our various holidays are not disappearing; on the contrary, they are being quietly expanded and extended instead.

Efforts to undermine every last vestige of Christian European culture are all too predictable. We tend to forget that Communism was a huge proponent of multiculturalism — at the expense of the host culture. “Christmas, as an official holiday, was banned under the Soviet occupation. … Despite these restrictions, Christmas was unofficially celebrated. … This became a nation-wide protest against Soviet ideology and atheist propaganda in general.” (Estonian Foreign Ministry, 1998) This growing resistance may look like a small thing but, like seeds, the best things come in small packages.

Efforts to undermine every last vestige of Christian European culture are all too predictable. We tend to forget that Communism was a huge proponent of multiculturalism — at the expense of the host culture. “Christmas, as an official holiday, was banned under the Soviet occupation. … Despite these restrictions, Christmas was unofficially celebrated. … This became a nation-wide protest against Soviet ideology and atheist propaganda in general.” (Estonian Foreign Ministry, 1998) This growing resistance may look like a small thing but, like seeds, the best things come in small packages.

LINKS:

- Why does solstice occur?

- http://pegasus.phast.umass.edu/a100/handouts/solstice.html

- Daily footage of solstice sunset (December 2 to January 31, 1999). Filmed from within Maeshowe tomb, Orkney, Scotland. (Maeshowe is on “Mainland” Island – also called Pomona) — see “Samhain” — Pomona was the Roman Goddess of fruiting trees

- http://www.geniet.demon.nl/maeshowe/ http://www.velvia.demon.co.uk/

- the scuttled fleet at Scapa Flow – excellent site – archival news reports This is a compelling tale. At the Armistice of WWI, the German fleet was detained at Scapa Flow in the Orkneys for months. Finally, the ships were scuttled, by the Germans themselves

- http://giraffe.rmplc.co.uk/eduweb/sites/jralston/rk/scapa/backgrnd.html

- Jesuit Fathers at Sainte-Marie among the Hurons multiculturalism in New France

- http://www.sfo.com/~denglish/wynaks/wn_stmar.htm

- Charles Dickens’ Christmas Carol

- http://www.literature.org/Works/Charles-Dickens/christmas-carol/

- O. Henry’s Gift of the Magi

- http://www.auburn.edu/~vestmon/Gift_of_the_Magi.html

- Hear Handel’s Messiah

- http://www.prs.net/handel.html#Messiah

- dispose of your Christmas tree like a pro!

- http://www.mindspring.com/~chadallen/tree/index.html

- Electronic “Redneck” greetings. Note – there is a charge for this white-bashing hate-fest — but it’s worth a (free) look.

- http://www.americangreetings.com/greetingcard/pd/esearch.pd?L2=10&L3=16&L4=100266&L5=200278

- I’m Dreaming of a White Trash Christmas — har har har — sneering “advent” calendar

- http://www.junta.com/advent/

- Throwing a light on Seasonal Affective Disorder (affects up to 10% of Alaskans?)

- http://www.psychiatry.ubc.ca/mood/md_sad.html

- Canada Post recommended mailing dates

- http://www.canadapost.ca/CPC2/corpc/newsrel/xmasint.html