A wise nation preserves its records, gathers up its muniments, decorates the tombs of its illustrious dead, repairs its great public structures, and fosters national pride and love of country by perpetual reference to the sacrifices and glories of the past. – Joseph Howe

1914, William C. Hopkinson, a Canadian Government immigration inspector, was standing at the Barrister’s entrance of the British Columbia Provincial Courthouse, his hands in his pockets, when one Mewa Singh stepped up to him, drew a nickel-plated .32 calibre revolver, and fired from point-blank range. The inspector sank to his knees, grabbing Mewa Singh around the thigh, only to receive another bullet in the region of his heart. Mewa clubbed him over the head with the revolver, held in his left hand, then he dropped it and transferred the snub-nosed revolver from his left hand to his right. Still firing, he jumped in the air and threw up his arm each time he fired.

The shots were heard by James McCann, the janitor of the court house, and MacDonald, Cewe and Sustum, who were standing in a group at the bottom of the stairs leading to the second floor, where the shooting took place. As the men started up the stairway, eight East Indians: Basant Singh, Sohan Lal, Jo Dwalla Singh, Sundar Singh, Kalvo Singh, Duleep Singh, Isher Singh, and Natha Singh, scattered in front of them. McCann seized Mewa in a grip that prevented him from getting away.

Mewa tried to shoot McCann, but the latter was too strong and several policemen came forward and disarmed Mewa before he could do further damage. By the time a doctor arrived, Hopkinson was dead. Mewa Singh merely said: “I shoot, I go to station.” Charged along with Mewa Singh as conspirators were Husian Rahim, Sohan Lal, and Balwant Singh. William Charles Hopkinson was born in Yorkshire in 1878, the son of Agnes and William Hopkinson.

Hopkinson senior, a sergeant in the British army, was transferred to Allahbad, India, where he served as sergeant instructor of volunteers. Young Hopkinson showed an amazing ability for languages, becoming fluent in Hindi, and possessing a working knowledge of Punjabi and Gurukhi. In 1904, Hopkinson became an instructor of police in Calcutta, and three years later he moved to Vancouver, where he was hired by the Canadian Government as an immigration inspector and interpreter.

He was still working for the Indian police, however, monitoring the activities of East Indian extremists living in British Columbia, and developing a network of pro-British Sikh informants. East Indians first arrived in British Columbia around 1898, when Sikh regiments had passed through Canada on their return from Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and had told their compatriots of British Columbia’s riches and opportunities. In 1891, the Canadian Pacific Railway introduced a trans-Pacific passenger service from Hong-Kong to Vancouver. Seeking to replace with East Indians passenger steerage lost after the Canadian government had raised the head tax on Chinese immigrants.

Vancouver 1897 – Diamond Jubilee – Hong Kong Regiment. Groups of Chinese, Japanese and Sikh military were also on board

On April 1, 1904, the vanguard of an East Indian influx reached British Columbia on a C.P.R. liner. Five Sikhs, with beards and turbans, and sporting light cotton European-style clothing arrived on the “Empress of India”. In March, ten more came on the “Empress of Japan” and each succeeding month brought two or three more. Most of the East Indian immigrants were Sikhs and they came from the same district in the central Punjab. They were rural people who had mortgaged their land at 10 or 12 per cent interest in order to raise their $65 fare to Vancouver. They came in expectation of wages 10 to 15 times as high as anything they could make in India. Most were illiterate and few spoke English.

Their own testimony was that they had been induced to come to Canada by letters from friends and relatives. The need for passage money created great opportunities for local loan sharks. Moneylenders in each of the larger centres of population in India acted as immigration agents for their own profit. They were good advisors and told prospective Indian immigrants of the wealth to be made in British Columbia. In return for the $65 to take their victims to Canada, they demanded and received interest at a rate of $5 per month. According to American statistics, 96 per cent of the East Indians were between the ages of 14 and 44 and most were between 20 and 29.

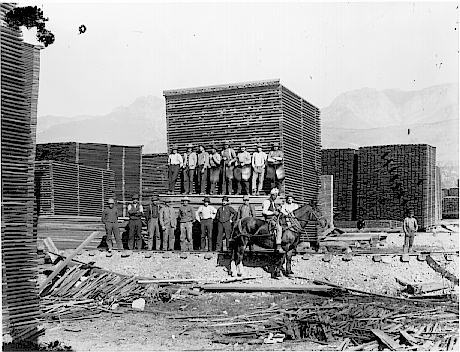

Perhaps 40 per cent were married and had left their wives in India. Once in British Columbia, the East Indians quickly gravitated to the lumber and sawmill industries, where they almost immediately acquired an unenviable reputation for violence and fractiousness. In the mills around Vancouver and Victoria they could make $1.50 or $2.00 a day, and live frugally, three or four to a room, on a sparse but adequate diet.

They saved most of what they earned. What they saved, they never banked, and in this way, some had accumulated $3,000 or more since their arrival in Canada. Their objective was always to go back to their villages, where even $200 would constitute a fortune. Under these circumstances, the trickle from India soon became a flood.

Sikh foreman on horseback – note lack of “racism”

Between January 1905 and January 1907, 3,969 East Indians entered the Dominion, while a further 2,623 arrived in 1908. Over one six-week period in late 1909, 1,447 Chinese, Japanese and East Indians landed on the shores of British Columbia, out of a total population that was only 392,480 in 1911. On January 8, 1908, the Canadian government passed two orders-in-council to deal with Indian nationals living abroad. One raised the sum of money required to be in possession of a prospective immigrant from $25 to $200.

The other authorized the Minister of the Interior to prohibit the entry of travellers unless they came directly from the country of their birth or citizenship. The “Continuous Journey” bill was specifically aimed at East Indians, there being no ticketing arrangements between India and Canada. The effect of these policies was that only 125 East Indians Canada between 1907 and 1912. In the first decade of this century, as a network of secret revolutionary societies spread from the Punjab and Bengal to Indian communities abroad, an intelligence organization grew apace.

This organization depended on secret service officers, not the least of which was William Charles Hopkinson. In intelligence matters, Hopkinson reported to the Deputy Minister of the Interior in Ottawa, and to J.W. Wallinger, Agent of the Government of India in London. He had access to criminal intelligence material from India that none of his Canadian superiors were supposed to see, and his connections were such that, in the United States, the American Commissioner-General of Immigration smoothed the path for his inquiries.

He drew an annual salary from the Canadian government, a stipend and expenses from the India Office, and a retainer from the American immigration service. All this had the approval of his superiors in the Department of the Interior. It was his job to keep tabs on the Indians, to know their movements and activities, and the more contacts he had the better he could do it; and it was a task that Hopkinson was eminently qualified to do. Tall — six feet, two inches — lean and dark, and a fluent speaker of Hindi, Hopkinson arrived in Vancouver from India around 1908 at the age of twenty-eight. He married an English stenographer, and fathered two daughters, Jean, who was born in 1908, and Constance, who was born four years later.

The Hopkinsons lived in a comfortable house in Vancouver, and Hopkinson soon became an immigration official, donning his uniform each morning and going about official business. He also led another life. In a poor immigrant neighbourhood in Vancouver, he also had a shack where he lived part of the time under the name of Narain Singh, leading the life of a penniless labourer from Lahore, wearing a turban and a false beard. Hopkinson attended meetings at the local Sikh temple, and paid other Hindus to tell him about the activities of immigrants he suspected, and for at least six years acted as an undercover agent in the immigrant community.

Hopkinson established an elaborate surveillance system within the local Sikh community. Offering his translating services to the United States immigration authorities in Vancouver and Montreal, in return for free entry into the United States for himself and his Indian informants: he was soon watching Indian activities on both sides of the border. He also provided U.S. immigration authorities with information on Indians entering the United States. Copies of his reports were sent to the Canadian government as well as to the British Colonial Office in London.

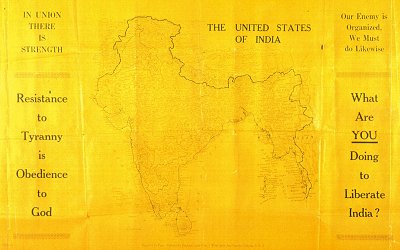

Hopkinson investigated and reported on many Indians between 1909 and 1914, but perhaps the two best known were Taraknath Das and Har Dayal, both of whom attempted to organize Sikh dissent against British rule in India.  Taraknath Das played a leading role in the formation of the Dacca Anusilan Samiti, a secret revolutionary society born in the midst of nationalist fervour which swept Bengal in 1905-1906. In January 1908, Taraknath opened a school for Sikh immigrants at Millside, near New Westminster. It was to be the local vehicle for the Hindustan Ghadr Party; which, although it originated in the United States, was active in Canada from the time of its creation. In and around San Francisco there arose a small group of Indian intellectuals who became the nucleus for growing anti-British sentiment. The party bought premises in San Francisco and began publishing a weekly paper called “Ghadr” which means “Revolution” in Urdu, its language of publication.

Taraknath Das played a leading role in the formation of the Dacca Anusilan Samiti, a secret revolutionary society born in the midst of nationalist fervour which swept Bengal in 1905-1906. In January 1908, Taraknath opened a school for Sikh immigrants at Millside, near New Westminster. It was to be the local vehicle for the Hindustan Ghadr Party; which, although it originated in the United States, was active in Canada from the time of its creation. In and around San Francisco there arose a small group of Indian intellectuals who became the nucleus for growing anti-British sentiment. The party bought premises in San Francisco and began publishing a weekly paper called “Ghadr” which means “Revolution” in Urdu, its language of publication.

It later appeared in other Indian languages, the largest number of editions being in Gurmukhi. In April 1908, Taraknath published the first edition of “Free Hindustani” in Vancouver. This was the original East Indian publication anywhere in Canada, and one of the first in North America. The violently anti-British English language monthly provoked a quick reaction when it began to appear in India, after 1,000 copies of the first edition were sent there.

Hopkinson may have been watching Taraknath long before his official agent began in 1909. It is possible that Hopkinson may have been sent to Canada by British India officials to watch just such student radicals as Taraknath. Born near Calcutta, he was one of the young Indians allowed by the British to receive a university education in order to qualify for the Indian civil service. Caught up in the anti-partition movement in 1905 to become “an itinerant teacher, explaining the economic, educational, and the political conditions to the masses of the people.” Taraknath was twenty-two when he arrived in Seattle on 16 July 1906, alone and broke. After working for a while as an unskilled labourer, he drifted down to California, where he worked in the celery fields, along with other Indians. Then, he worked in a hospital and read books in his spare time, until a professor of medicine helped him to get work in a laboratory at the University of California at Berkeley. He enrolled as a student and tried to file a Declaration of Intention to become an American citizen, and after being turned down, he took a competitive examination for the position of translator with the United States immigration service. His rating won him a job in Vancouver in 1907. Working closely with Taraknath was Guru Dutt Kumar, a native of Bannu in the Northwest frontier of India. Kumar was briefly an instructor in Hindi and Urdu at the National College in Calcutta, where he stayed at Marathe Lodge, a boarding house and gathering place for revolutionaries. It was there that Kumar met Taraknath, and it was with Taraknath’s help that Kumar set up a grocery store in Victoria soon after his arrival in October, 1907. In December 1909, Kumar opened up the “Swadesh Sewak” meaning “Servant of the Country”, in Vancouver. It served as home for revolutionaries that fronted as a night school with studies in English and mathematics for Sikh immigrants. Kumar was also active in establishing the Hindustani Association, the first overtly political East Indian organization in Canada. By that time, Kumar had been eclipsed locally by Kairai Varma, a forty-eight-year-old Hindu from Porhander state in Gurjarat. Varma lived for a number of years in Japan, before running into financial difficulties and absconding to Honolulu under the Muslim name of Husain Rahim. There he was arrested and ordered deported nine months later. While at the police station, he was searched and found to possess a notebook containing a recipe for the manufacture of nitro-glycerine and the addresses of East Indian revolutionaries in the U.S., France, Natal, and elsewhere.

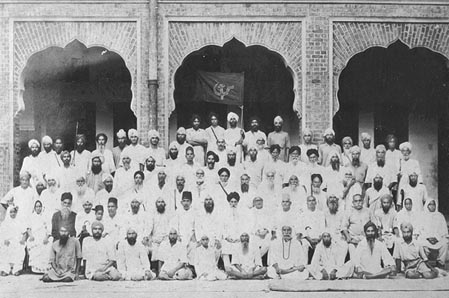

In 1929, while presiding over the All India Sikh Conference, held in Lahore, veteran freedom fighter Baba Kharak Singh said: “We the Sikhs shall never allow any foreigner to rule over our Motherland, and we shall brook no injustice”. Early in 1911, Varna was joined by Lal Har Dayal, an intellectual and radical who had just resigned a British scholarship to Oxford, protesting his disapproval of colonial rule in India. In mid 1913 a meeting was held in Oregon to form an umbrella orgaization, uniting Hindus in Canada and the United States, known as the Hindu Association of the Pacific Coast.

In 1929, while presiding over the All India Sikh Conference, held in Lahore, veteran freedom fighter Baba Kharak Singh said: “We the Sikhs shall never allow any foreigner to rule over our Motherland, and we shall brook no injustice”. Early in 1911, Varna was joined by Lal Har Dayal, an intellectual and radical who had just resigned a British scholarship to Oxford, protesting his disapproval of colonial rule in India. In mid 1913 a meeting was held in Oregon to form an umbrella orgaization, uniting Hindus in Canada and the United States, known as the Hindu Association of the Pacific Coast.

Sohan Singh Bhaka and Lal Har Dayal were elected president and secretary, respectively. By November, 1913, the Ghadr Party was formally organized to promote national independence for India. East Indians in the United States and Canada immediately pledged $200 to set up a national publishing centre in San Francisco. The first issue of the Ghadr Party newspaper stated the objectives of the party in the following terms: “Today, there begins, in foreign lands, but in our country’s language, a war against the British Raj. What is our name? Ghadr. What is our work? Ghadr. Where will Ghadr break out? In India. The time will come when rifles and blood will take the place of pen and ink.”

Hindu settlers in Canada, Japan, the Philippines, Hong Kong, China, the Malay States, Singapore, British Guiana, Trinidad, British Honduras, South and East Africa, and other countries where there were Indian communities. Thousands of copies were also sent to India. Taraknath Das’ activities had attracted the attention of T.R.E. McInnes, who had been delegated by the Superintendent of Immigration to keep an eye on the local East Indian community. The possibility of local sedition also engaged the interest of William Hopkinson. Hopkinson identified Rahim, Kumar and Taraknath as advocates of violence. In the spring of 1908, Hopkinson went to the Canadian and British press and described how the seditious movement in India was being directed from the Pacific coast of North America, and how the Hindu school at Millside was the centre of revolutionary activity.

Hopkinson’s actions forced the Canadian government to close the Millside school. Later, Rahim was arrested, and at his trial he turned to Hopkinson and exclaimed vehemently: “You drive us Hindus out of Canada and we will drive every white man out of India.” He was judged innocent at the time. At a meeting at the Sikh temple, which was located at 1866 Secord Avenue West in Vancouver, on December 27, 1913, Hussain Rahim, acting as chairman, informed the audience that he had started a newspaper to oppose H.H. Stevens, Member of Parliament for Vancouver Centre, and the province’s leading advocate of Asiatic exclusion. He added that he hoped that some of those present: “Would fix the three or four traitorous Hindus who are leagued with the immigration authorities of this province.”

Then, Kanshi Singh read a poem, written by himself, and accusing Bela Singh, Baboo Singh, Ganga Ram, and immigration inspectors Reid and Hopkinson of being enemies of the East Indians in Canada, and calling for their assassinations.

Gurdit Singh Sarhali Gurdit Singh Sarhali was born and raised in Amritsar, the Sikh holy city in the Punjab. He had attended British-run schools up to the university level and then immigrated to Singapore, where he was engaged in the contracting business, both there and in the Malay States. Gurdit possessed two interesting traits; a dislike for British rule in India, and an avaricious appetite for money.

Despite his pious mumblings, he devised a scheme to both enrich himself and to embarrass the British and Canadian governments. He planned to establish a steamship line from Calcutta to Vancouver, carrying East Indians on their voyages, then returning to India with cargoes of lumber. He believed that the $200 that each prospective immigrant was required to possess in order to enter Canada, could be raised by the local East Indian community upon the arrival of each immigrant. In March 1914 he began selling tickets in Hong Kong, and shortly afterwards used the proceeds to charter the steamship “Komagata Maru” for six months, for sixty thousand Hong Kong dollars.

Passive passengers under repressive armed guard? Canadians have forgotten the Komagata Maru and murder of Hopkinson , but the incident is alive, well, and still being spun “back home”. Punjab and Sind Bank Calendar – 1989

The ship left Yokohama on May 3, 1914 and arrived, with its cargo of 376 illegal immigrants, in Victoria harbour eighteen days later.

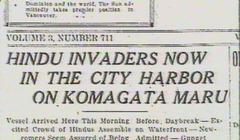

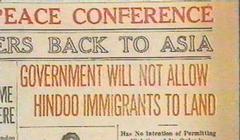

“Hindu” was a generic term – as was East Indian (now South Asian) At 11 a.m. on May 22, 1914, pilot Barney Johnson anchored the steamship “Komagata Maru” off Number 2 berth in Vancouver harbour. The arrival of the “Komagata Maru” in Vancouver produced a storm of protest throughout British Columbia. H.H. Stevens M.P., asked for and received a renewal of the government’s ban on artisans and labourers. In Vancouver, immigration officials asserted that the East Indians would not be let in.

The residents of Vancouver were, with few exceptions, violently opposed to the admission of Asiatics, as had been shown by the actions of 1887 and 1907. (See The Workingman’s Revolt: The Vancouver Asiatic Exclusion Rally of 1907 by Robert Jarvis – CFAR Books, $5.00) The admission of the men on the “Komagata Maru” could have provoked an outbreak more violent than ever before, for the city had grown in numbers and the opposition was stronger and more widespread.

Awaiting clearance By the second week in June 1914, Gurdit Singh found himself in an increasingly difficult situation. The passengers that he had brought to Vancouver were becoming increasingly restless and dissatisfied with his leadership. The East Indians were without money to pay for provisions and were depending on the benevolence of the local East Indians for their daily sustenance. It cost $200 a day to supply the immigrants with food and other necessities.

The vessel had already incurred a debt of approximately $18,000. In addition, each passenger had paid Gurdit Singh $100 cash as passage money, which was almost double the price of a third-class passage on a C.P.R. steamer from Hong Kong. H.H. Stevens returned to Vancouver on the morning of June 14, when Parliament recessed. He stated that he had been strongly urging the government to adopt a plan which would involve the control of immigration to Canada in the hands of Indian authorities. When asked how the situation stood at present he replied: “The Dominion authorities are absolutely determined that the law with reference to the admission of Hindus shall be strictly enforced.” The delay in returning the “Komagata Maru” was caused, in Stevens’ opinion: “By the belligerent attitude adopted by the Hindus themselves who are trying to evade the regulations.” King George V, replying to a telegram sent on behalf of the “Komagata Maru” passengers, said that the matter was entirely in the hands of the government of Canada.

Public opinion in the United Kingdom, judging from the editorial statements made by the leading newspapers of London, supported the proposition that the British government could not interfere in the regulation of immigration into Britain’s Dominions. On the morning of June 24, 1914, the most serious development in the proceedings surrounding the passengers of the “Komagata Maru” was reported from Ottawa. The government intended to let them land and to test their right of entry in the courts. A thoroughly alarmed H.H. Stevens declared that he: “Would oppose any such move to the limit.

The landing of these Hindus would be much more likely to cause riots than keeping them where they are. If the event proves that the government intends to lands them temporarily, as is stated in the despatch, it is probable that the Vancouver citizens will turn out and prevent such a landing. They had experience of this proposition on a previous occasion, [the events of 1907] and do not want that experience to be repeated.”

Other vessels were dwarfed by the steamer Meanwhile, an attempt was made by Rahim Singh, Balwant Singh, a priest, and Bag Singh, head of the United Hindu League, to board the “Komagata Maru”. Immigration officials increased their watchfulness, and one of the patrol boats remained constantly by the ship. The possibility of an imminent landing of East Indians from the “Komagata Maru” sparked a series of spontaneous meetings in different parts of Vancouver and surrounding areas. On the night of June 29, the Vancouver City Council adopted a resolution introduced by Alderman McHeath, protesting the ship’s landing in Canada. On the morning of July 6, 1914, in a crowded and dingy Court of Appeal, Chief Justice MacDonald made a brief statement.

He said that the Court of Appeal had unanimously upheld the steps taken by the immigration authorities in preventing the landing of the “Komagata Maru” passenger, Munshi Singh, on the following grounds: First, that he was a native of India and did not possess the $200 required, secondly, he was an immigrant who had come to Canada in a manner other than a continuous journey from his native country, and lastly, that he was an unskilled labourer. On all three points, the five members of the court were unanimous. In effect, the decision of the Court of Appeal meant the end of Asiatic immigration into Canada for half a century.

Hardly a “Continuous Journey” Gurdit Singh and his “Committee of Safety on the ‘Komagata Maru'” agreed to drop their fight for entry into Canada, and were expected to steam out of Burrard Inlet by the end of the week. An important conference was held on board the vessel on July 7, between W.H.D. Ladner, counsel for the Dominion Government, Mr. J. Edward Bird, counsel for the East Indians, and William Hopkinson. Gurdit Singh and the passengers on board, while deeply resenting the judgement of the court against them, seemingly accepted the verdict without any hostility and they reported that their only anxiety was that they be permitted to sail at the earliest possible opportunity to their homes. As the day was approaching for the ship to leave Canadian waters, there was more trouble.

The passengers took control of the ship from Captain Yamamoto and his crew. Yamamoto sent a letter to Chief of Police McLennan asking the police to help him regain control of his vessel. The Dominion Government instructed Superintendent Reid of the Immigration Department to take a firm hand at once; to subdue the East Indians of the “Komagata Maru”, and to send the steamer back to Asia. On the afternoon of July 18, 1914, immigration officers W.D. Ladner and R. Reid discussed the ship’s matters generally. Ladner told Reid that the ship was to be taken by police that evening. Police and immigration forces would take possession of the ship, while the local militia would remain on the wharf to await emergencies.

The tug “Sea Lion” with one hundred and twenty-five Vancouver city policemen and thirty-three special immigration police aboard, reached the “Komagata Maru” at one o’clock on the morning of the 19th. At that moment it became obvious that the deck of the “Sea Lion” was fifteen feet below the deck of the “Komagata Maru”, giving a tremendous advantage to the East Indians in the fight that was soon to follow. The attacking force, acting with courage and determination, was met with a fusillade of coal, bricks, and scrap iron. The light of the “Sea Lion” blazed on naked sword blades and on one or two rifle barrels. One man, Harnam Singh, had a revolver, a souvenir of his service with the Indian Army, but most of the East Indians were armed with ten-foot bamboos, others had long iron bats and large knives. A voice hailed from the “Komagata Maru”, asking for Inspector Hopkinson, and an exchange in Punjabi took place.

On board the Sea Lion – H.H. Stevens centre – Hopkinson on the right What was to become known as the Battle of Burrard Inlet was in progress. Howling masses of East Indians, encouraged by a Sikh priest and a Hindu Mullah, continued to pelt the deck of the tug with missiles. Men began to go down onto the crowded decks, and a seam of wounded men staggered into the captain’s cabin for medical attention. Suddenly four shots rang out. Harnam Singh was firing his revolver at H.H.

Stevens and William Hopkinson. Amazingly, none of the authorities, in the heat of the action, disobeyed the pre-attack order to refrain from shooting. Fifteen minutes after the beginning of the battle, the “Sea Lion” backed away from the steamer’s side and returned to the pier. The East Indians yelled more loudly than ever and promised: “to cut the hearts out of any dogs of the white race who came aboard the ‘Komagata'”.

The police had intended to take possession of the “Komagata Maru” and had been repulsed. The problem of the ship and its illegal cargo remained. The solution to the problem was the H.M.C.S. “Rainbow”. The “Rainbow”, an “Apollo” class cruiser used as a training ship by the R.C.N., was both run-down and dramatically undermanned. Quietly, steps were taken to put the “Rainbow” in condition to be used, if the need arose. By July 20 she was made ready and on the morning of the 21st she slipped quietly into Burrard Inlet and anchored near the “Komagata Maru”.

On the morning of July 23, 1914, the “Komagata Maru” left her anchorage in Burrard Inlet. (See The ‘Komagata Maru’ Incident by Robert Jarvis, C-FAR Books, 1992) Five days later, Austria declared war on Serbia, and Canada, with the rest of the British Empire, was at war.

When the ship returned to India, the passenger’s refusal to return to the Punjab led to yet another riot (at Budge-Budge, outside Calcutta) where 29 were shot. Punjab and Sind Bank calendar – 1989 While the “Komagata Maru” and the returning Hindus were making their way back to Asia, a series of spectacular events rocked the East Indian community in Vancouver. The “Komagata Maru” incident was the last straw in the rising hatred against the small group of informants in the employ of William Hopkinson. By then they had incurred the wrath of both the revolutionaries and the religious Sikhs who felt that their intelligence activities violated the spirit of the “Khalsa”.

On August 17, Harnam Singh vanished, only to be found murdered at the end of the month. He had been an underling of Bela Singh, one of Hopkinson’s key infomants. Soon thereafter, Arjan Singh, another Sikh in the employ of the government, was shot dead by Ram Singh, an elderly, religious man who had not been visible before. He was tried and acquitted for the death of Arjan Singh. On September 5, the body of Arjan Singh was cremated.

This was followed by an evening memorial service in the Vancouver temple. Approximately 50 people participated, including Bela Singh, who sat directly behind Bhag Singh, who was leading the service. Twenty minutes later, he began shooting, first at Bhag Singh, then at others. Nine individuals were shot, and Bhag Singh and Bhattan Singh were mortally wounded. A hundred Sikhs crowded into the hearing for Bela Singh, and he was bound over for trial. The tense situation was exacerbated when Hopkinson’s informants Gunja Ram and Babco Singh uncovered a bomb-manufacturing operation in Victoria. As the October 21st date for Bela Singh’s trial approached, plans were made to ensure that Hopkinson would be assassinated.

Mewa Singh, one of the Sikhs that was apprehended for gun-running, offered to kill Hopkinson. The body of William C. Hopkinson was cremated at Mountain View Cemetery on the afternoon of October 24, 1914, having been followed by one of the largest funeral processions ever seen in Vancouver. More than two thousand people took part, as a mark of respect for Hopkinson. Long before the hour of the funeral, the street in front of the police station was crowded with silent people. Rev. C.C. Owen and Rev. J. Knox-Wright read scripture and recited prayers.

Rev. Dr. Fraser spoke briefly about the life and the example of the man who had done his duty. The funeral procession formed with a corps of mounted police in advance, followed by the 6th Regimental Band, and a company of that regiment, to which Hopkinson had belonged. Next came one hundred and eighty hand-picked policemen, followed by one hundred firemen. Several hundred members of the Orange Lodge preceded the hearse and flower-laden cars.

The U.S. Immigration Department, the C.P.R. police, post office employees and Customs House officials all took part. The procession travelled up Hastings to Granville Street, to Georgia Street, and then down to Homer Street, where the lines opened and let the hearse and vehicles through.

Site of the Komagata Maru plaque – ironically on Hastings Street – the route of Hopkinson’s funeral procession

According to information given to the police by friendly East Indians, a meeting was held in New Westminster the night before the funeral, at which a large number of East Indians were present, and three of their number were selected by lot to shoot Superintendent Reid and Chief of Police McLennan at the funeral. Every East Indian along the route was covered by a plainclothesman, with the muzzles of their revolvers bulging in their pockets. At the conclusion of the funeral, H.H. Stevens received a telegram from the Department of the Interior, ordering that all expenses incurred for the funeral be forwarded to Ottawa, where payment would be made. The trial was held on October 29, 1914. Sitting in the dock at the police court, the accused listened attentively to the evidence. He pondered for a few minutes, then declared that he did not retain counsel, but that if his friends saw fit to do this on his behalf, he would be pleased. Formal evidence was given by the physician who had conducted the post-mortem examination.

Four bullet holes were found in the deceased; in the chest, knee and back. After a trial that lasted two hours, the jury deliberated for five minutes. Mewa Singh was convicted, and was sentenced to be hanged on January 11, 1915. After his execution, his body was taken in a procession through the city and was cremated with great honour. In the months following the murder of Hopkinson and the execution of Mewa Singh a period of relative peace settled on Vancouver’s usually turbulent Sikh community. But on May 13, 1915, there was a terrific explosion at 1748 West 3rd Avenue in Vancouver. Mehtab Singh was killed and Dulip Singh and Pritam Singh were critically injured.

All three had been members of Bela Singh’s faction during the “Komagata Maru” incident. One result of the “immigration revolution” of the 1960s has been an enormous increase in non-traditional immigration into Canada; including large numbers of Sikhs. These immigrants, like Kurds and other immigrants, insist in bringing the endless quarrels taking place in their benighted homelands to Canada. In the early 1980s, a Sikh, Kuldip Singh Samra, opened fire in a Toronto court room, killing one man and paralyzing another. In 1986, four Sikhs tried to assassinate a visiting state minister from the Punjab. It was a Sikh, too, who was convicted of making a bomb planted on a flight to Tokyo, which killed two baggage handlers at Narita Airport.

Only by luck was a tragedy avoided similar to the one that downed an aircraft off the coast of Ireland, in which 329 people were killed. In 1988, Tara Singh Hayer, a moderate Sikh journalist in Vancouver was shot and wounded by a radical Sikh gunman. In November, 1998, he was murdered. A Sikh murdered nine people at a wedding in Vernon, the main victim being his estranged wife. When Sikh bodyguards killed Indian Prime Minister Indira Ghandi, local Sikhs danced in the streets.

Mewa, the “martyr” Today, Mewa Singh, the terrorist and the murderer of William Hopkinson, is hailed as a hero by many in the Sikh community. The main recreation room in the Ross Street Gurdwara, is named in his memory. The date of his execution is commemorated annually by the Sikh community with a large ceremony, and is known as Mewa Singh Martyr Day.

Robert Jarvis

Plaque at the Gateway to the Pacific park – inscription as follows – On May 23, 1914, 376 British Subjects (12 Hindus, 24 Muslims and 340 Sikhs) of Indian origin arrived in Vancouver harbour aboard the Komagata Maru, seeking to enter Canada. 352 of the passengers were denied entry and forced to depart on July 23, 1914. This plaque commemorates the 75th anniversary of that unfortunate incident of racial discrimination and reminds Canadians of our commitment to an open society in which mutual respect and understanding are honoured, differences are respected, and traditions are cherished. TRANSLATION: Heroes are for other people – Life is ugly and hopeless – Canadians deserve to be replaced

See The ‘Komagata Maru’ Incident by Robert Jarvis, C-FAR Books, 1992 LINKS Are politicians merely ignorant of the real events — or worse? As B.C.’s odious NDP government tried to pick provincial pockets over the Nisga’a Treaty, they called on all the gods of guilt and multiculturalism for guidance …

[ Page 11004 ] “Whether it was through the Komagata Maru incident and the time that we turned back people of Indo-Canadian ancestry…” Hon. Glen Clark (Premier) 1998 Legislative Session: HANSARD Volume 12, Number 25 THURSDAY, DECEMBER 10, 1998

[ Page 10931 ] “…and for Indo-Canadians, the Komagata Maru incident, where they couldn’t land their people here because of racism and discrimination.” Hon Ian Waddell, 1998 Legislative Session: HANSARD Volume 12, Number 21, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 8, 1998

Some stats on Sikh militarism. Interesting, in light of the interminable Canadian Legion vs. turban debate, is point #

4. These forces “Freies Indien” arm badge fought in German uniform as the Free India Legion, or Indische Legion der Waffen-SS.

Canadian politicians – busy building a nation of witless hypocrites

While Canadian politicians appeared in turbans for the “300th”, back in India, police battened down the hatches fearing mayhem.

The Party Line – “Politics of Exclusion” Immigration Canada “discriminates” in requesting identifiable last names? Terrorism – U.S. Dept. of State The Ghadar movement

Vancouver B.C. site – breathtakingly contemptuous attitude toward Hopkinson. Callously forgotten by Canada, he is callously dismissed here as “a corrupt officer”

Read all about “the fake propaganda made by the Canadian government against their community” and “the desecration of their temple (Gurdwara Sahib) by the entry of a white man”.

In this version, the Komagata Maru sails to the US: a fortunate Hopkinson survives WWII, and his actions alone inspire the Ghadar Movement (Duke of Connaught’s Own) British Columbia Regiment Reht Maryada – Code of Sikh Conduct and Conventions

“If I came across [the US border from Mexico] wearing a turban and beard I would get arrested. I would die for my faith, but I didn’t want to be deported for it.” Sacramento Bee, 11/11/91 (this is under the Berkeley pioneer Asian immigration site – the Mexican Sikhs)

Immigration – the double-edged sword Stamp issued by Canada Post April 19, 1999

The two opening poems in Sadhu Binning’s No More Watno Dur are about the Komagata Maru:

The Heart-Breaking Incident at the same shore of the ocean where once stood Komagatu [sic] Maru and went back without kissing the shore sand shrieking like a hungry elephant facing the guns now sitting amidst the driftwood, the gravel, the sand I wonder how they witnessed the scene and listened to the voices of our grandfathers I try to enjoy the music of the waves but only the angry Punjabi voices from the Maru reach my ears I ask the waling stones about the heartbreaking incident they laugh turn their faces and walk away ———- and the follow-up poem Welcome I often speak to the grass the trees and the river they never tell me I wasn’t welcome I’ve heard the wind chatting with leaves not once a note of hatred the rain and the snow touch me on my shoulders as many other friends do the birds come every morning and sing outside my window welcoming me into a new place a new day why weren’t they consulted when the decision was made to send my Komagatu [sic] Maru away.

Sadhu Binning teaches Punjabi at the University of British Columbia (“Watno Dur” in Punjabi means “far from the homeland.”)