“AN HONEST MAN’S THE NOBLEST WORK OF GOD” ROBBIE BURNS AND THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES  Humanist, humourist and patriot — Robbie Burns died in 1796. By 1801, a group of Ayrshire men were already honouring their friend at an annual dinner. This year, on the 239th anniversary of his birth, thousands of men and women will toast the immortal memory and drain a glass or two. When they do, they’ll be furthering a cause that was near and dear to his heart. He held inebriation in high regard as he remarked: “Whiskey and freedom gang thegither”. Imbibing a wee dram would have enhanced many of the things he loved best: sociability, earnest argument, music, dancing and, of course, the lassies! These shameless flirtations were so successful that he and his long-suffering wife raised at least three of his illegitimate children in the family home.

Humanist, humourist and patriot — Robbie Burns died in 1796. By 1801, a group of Ayrshire men were already honouring their friend at an annual dinner. This year, on the 239th anniversary of his birth, thousands of men and women will toast the immortal memory and drain a glass or two. When they do, they’ll be furthering a cause that was near and dear to his heart. He held inebriation in high regard as he remarked: “Whiskey and freedom gang thegither”. Imbibing a wee dram would have enhanced many of the things he loved best: sociability, earnest argument, music, dancing and, of course, the lassies! These shameless flirtations were so successful that he and his long-suffering wife raised at least three of his illegitimate children in the family home.

He may have scandalized polite society, but despite, or perhaps because of, that, he had a phenomenal way of raising people’s spirits and making them glad. He emphasized decency in a world that barely knew it, and fostered a sense of dignity and self worth in his all but broken people. When he realized that Scottish songs and folk tales were in a state of decline, he devoted himself to collecting and codifying a good portion of what survives today — over 350 songs alone. A recognized national treasure by the end of his life, his stature as poet laureate of Scotland the Brave has never been seriously threatened. His debut could hardly have been more modest: blown in on “a blast of Janwar’ win'”, he was born in his mother’s kitchen on January 25, 1759. For a’ that, Robbie and six younger children were to receive unusually fine educations for the brood of an impoverished tenant farmer. Their tutor’s lessons in English literature, French and dancing were augmented by his illiterate mother’s encyclopaedic knowledge of Scottish folklore. As he remembered it, “Though I cost the schoolmaster some thrashings, I made an excellent English scholar”.

His Times

Burns’ contribution is all the more remarkable when we place him in the grim context of his times. This man who would breathe life into Scottish utterance and give it an enduring legitimacy, was born in an age when his culture, his heritage, his very people, were despised to the point of prohibition. To this day, the frenzied genocidal policies enacted against the Highlanders receive faint mention in official histories and remain largely unknown outside Caledonian circles. If any of this has a familiar ring to Christian European ears, read on. In his gentle poem, “The Wounded Hare”, one wonders whether Robbie is referring to the poor mangled beastie, or to betrayed Highlanders, badgered, beaten and brutalized into silence?

The Wounded Hare

Inhuman man! curse on thy barb’rous art, And blasted be thy murder-aiming eye; May never pity soothe thee with a sigh, Nor ever pleasure glad thy cruel heart! . Go live, poor wanderer of the wood and field! The bitter little of life that remains: No more the thickening brakes and verdant plains To thee shall home, or food, or pastime yield. . Seek, mangled wretch, some place of wonted rest, No more of rest, but now thy dying bed! The sheltering rushes whistling o’er thy head, The cold earth with thy bosom prest. . Oft as by winding nith, I musing, wait The sober eve, or hail the cheerful dawn; I’ll miss thee sporting o’er the dewy lawn, And curse the ruffian’s aim, and mourn thy hapless fate.

Inhuman man! curse on thy barb’rous art, And blasted be thy murder-aiming eye; May never pity soothe thee with a sigh, Nor ever pleasure glad thy cruel heart! . Go live, poor wanderer of the wood and field! The bitter little of life that remains: No more the thickening brakes and verdant plains To thee shall home, or food, or pastime yield. . Seek, mangled wretch, some place of wonted rest, No more of rest, but now thy dying bed! The sheltering rushes whistling o’er thy head, The cold earth with thy bosom prest. . Oft as by winding nith, I musing, wait The sober eve, or hail the cheerful dawn; I’ll miss thee sporting o’er the dewy lawn, And curse the ruffian’s aim, and mourn thy hapless fate.

The Proscriptions

The movie Braveheart deals with events surrounding the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn, where Scots defeated Edward Longshanks’ numerically (by three-to-one) superior English forces. This victory would prove to be short-lived. Successive English kings had no liking for those they viewed as barbaric Gaels and felt there could be no English ease so long as the Scots saw themselves as a distinct nation. The official chronicler at Wallace’s execution had gloated: “He was hung in a noose, and afterwards let down half-living; next his genitals were cut off and his bowels torn out and burned in a fire; and then and not till then his head was cut off and his trunk cut into four pieces.” Wallace’s head was displayed on London Bridge like a hunting trophy. These rancorous events, known to every Scot, festered over long centuries. The 1710 Act of Union suppressed Scotland’s Parliament and independence as a separate political entity. The Black Watch was raised in 1725 to keep an eye on these northern ruffians. During the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion, when Bonnie Prince Charlie Edward Stuart’s army marched as far as Derby in the Midlands, you may imagine how the Hanoverian king (so well accustomed to winning battles elsewhere) greeted the news. The following year Scottish and English forces met at Culloden , where the  Highlanders (now outnumbered just two-to-one) lost 1,200 and the government 76. This stiffened royal resolve to once and for all break the great clan system.

Highlanders (now outnumbered just two-to-one) lost 1,200 and the government 76. This stiffened royal resolve to once and for all break the great clan system.

http://members.aol.com/heather130/ats.html However, the ancient symbiotic relationship between Scottish landowner and landless tenant was crumbling already, succumbing, as usual, to greed. In 1739, MacDonald of Sleat and Macleod of Dunvegan had broken the bond, when they sold tenant farmers into indentured servitude, bound for the Carolinas. Over a thousand survivors of Culloden were rounded up and sent to Barbados to end their days, not in indentured servitude, but as actual slaves.Yes, Whites were slaves! Public executions and appropriation of the Jacobite anthem (reworked into God Save the King) reinforced the message. In his “On the Occasion of National Thanksgiving”, Burns gave full vent to his admiration. Reduced to working as an excise man, (tax collector), he never acknowledged some of the vitriol that flowed from his sharp pen, but, as you see , he sold his services, not his soul.

Ye hypocrites! are these your pranks? To murder men, and gi’e God thanks! For shame! gi’e o’er, proceed no further – God won’t accept your thanks for murder!

In the wake of Culloden, Parliament enacted “The Proscriptions”. Robbie Burns was born in his mother’s poor kitchen a dozen years into these genocidal policies, and they remained in force over most of his lifetime. Under the Proscriptions, it was illegal for a Highlander to own a horse worth more than two-pounds. It was illegal for a Highlander to wear the kilt or a plaid (the “plade” is the great swath of cloth that makes kilt or cloak). The plaid was ideally suited to carrying out guerrilla warfare from the hills.In the opening scenes of Rob Roy, you s

In the wake of Culloden, Parliament enacted “The Proscriptions”. Robbie Burns was born in his mother’s poor kitchen a dozen years into these genocidal policies, and they remained in force over most of his lifetime. Under the Proscriptions, it was illegal for a Highlander to own a horse worth more than two-pounds. It was illegal for a Highlander to wear the kilt or a plaid (the “plade” is the great swath of cloth that makes kilt or cloak). The plaid was ideally suited to carrying out guerrilla warfare from the hills.In the opening scenes of Rob Roy, you s ee the men making the best use of them as they track their cattle. “The Time of the Grey” outlawed even the traditional bright colours of the tartans. Highlanders were not allowed to gather in an effort to suppress “the nurseries and schools of rebellion” . It was illegal to teach the written Gaelic language. The Disarming Act of 1746 forbade Highlanders from owning a Claymore or other weapon and rendered the summary search for them legal. The Great Highland Bagpipe, so capable of stirring men’s blood and spurring them to valorous deeds, was likewise outlawed as an “Instrument of War”. The Highlanders resisted where they could, but people can be beaten, cajoled, starved and bred out of their beliefs. In remote caves along the sea-coast, you might have heard the older people quietly “singing” the old piping tunes to the young ones to keep the music alive. It is from this tradition that “Pibroch”, [pea-brook] the old, classical form of piping music, survives. The penalty for breaking any of these laws was seven years transportation “to any of His Majesty’s plantations beyond the sea.” Ironically, in the 50 years that followed Culloden, 22 splendid Highland regiments were raised for the Crown, but then, joining a regiment was the one and only exemption to the Proscriptions. To a warrior breed, the moral dilemma posed by donning the despised government’s black tartan might not have been as keenly felt as the sharper pangs of starvation. Here in the regiments, one could at least wear the plaid, carry a weapon — and eat.

ee the men making the best use of them as they track their cattle. “The Time of the Grey” outlawed even the traditional bright colours of the tartans. Highlanders were not allowed to gather in an effort to suppress “the nurseries and schools of rebellion” . It was illegal to teach the written Gaelic language. The Disarming Act of 1746 forbade Highlanders from owning a Claymore or other weapon and rendered the summary search for them legal. The Great Highland Bagpipe, so capable of stirring men’s blood and spurring them to valorous deeds, was likewise outlawed as an “Instrument of War”. The Highlanders resisted where they could, but people can be beaten, cajoled, starved and bred out of their beliefs. In remote caves along the sea-coast, you might have heard the older people quietly “singing” the old piping tunes to the young ones to keep the music alive. It is from this tradition that “Pibroch”, [pea-brook] the old, classical form of piping music, survives. The penalty for breaking any of these laws was seven years transportation “to any of His Majesty’s plantations beyond the sea.” Ironically, in the 50 years that followed Culloden, 22 splendid Highland regiments were raised for the Crown, but then, joining a regiment was the one and only exemption to the Proscriptions. To a warrior breed, the moral dilemma posed by donning the despised government’s black tartan might not have been as keenly felt as the sharper pangs of starvation. Here in the regiments, one could at least wear the plaid, carry a weapon — and eat.

The Clearances

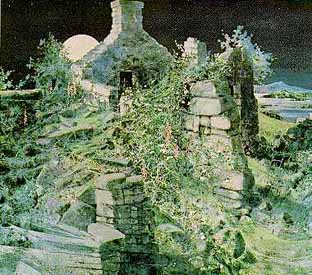

Yet, the destruction of Highland culture was just the beginning. When the English Government enacted the 1747 “Heritable Jurisdictions Act”, troublesome Highlanders who would not accede to English terms saw their lands seized and turned over to government appointe “administrators”. What land remained in the hands of the chieftains was to become the vehicle of an even greater betrayal of the people — by the lairds themselves. When  the Proscriptions were finally repealed in 1782, economic conditions were already shepherding in the final, calamitous blow. In 1801, Highland wool sold for 15 shillings per stone (or 14-pound-weight). By 1818, the price had more than doubled, to 40 shillings per stone. The surviving chieftains came to realize that where they had once reckoned 500 tenant farmers (and potential warriors) a blessing on the land, these men and their families were, overnight, liabilities. Under the old system, “rent” had been paid out in fealty to the laird; his clan’s willingness to scream into battle under his pennant had entitled them to scrape a meagre living from a stingy land. However, soon the chieftains were demanding rents, enforcing evictions, and replacing “unproductive” men with Cheviot sheep. And the people just didn’t get it. Their Gaelic worldview was based on kinship. Clan meant family — to them. Homes, livestock, even furnishings, were seized in lieu of unpaid rents. The houses’ roof-poles were deliberately put to the torch and, in the treeless Highlands, this meant no further shelter on ancestral lands. People burned to death in their ruined crofts, or crawled back into them to die.

the Proscriptions were finally repealed in 1782, economic conditions were already shepherding in the final, calamitous blow. In 1801, Highland wool sold for 15 shillings per stone (or 14-pound-weight). By 1818, the price had more than doubled, to 40 shillings per stone. The surviving chieftains came to realize that where they had once reckoned 500 tenant farmers (and potential warriors) a blessing on the land, these men and their families were, overnight, liabilities. Under the old system, “rent” had been paid out in fealty to the laird; his clan’s willingness to scream into battle under his pennant had entitled them to scrape a meagre living from a stingy land. However, soon the chieftains were demanding rents, enforcing evictions, and replacing “unproductive” men with Cheviot sheep. And the people just didn’t get it. Their Gaelic worldview was based on kinship. Clan meant family — to them. Homes, livestock, even furnishings, were seized in lieu of unpaid rents. The houses’ roof-poles were deliberately put to the torch and, in the treeless Highlands, this meant no further shelter on ancestral lands. People burned to death in their ruined crofts, or crawled back into them to die.  At the height of the “Highland Clearances”, it was not uncommon for 2,000 houses to be burned in a single day. Scotland was soon awash in a tide of heartsick, vagrant people. In the way of all disasters, not one thing — but everything — conspired in the ruin: recurrent outbreaks of cholera, widespread tuberculosis, frequent crop failures and food shortages all seemed like minor annoyances when, in the spring of 1846, spores came drifting over the land. The Irish potato blight brought long years of famine. All in all, Highlanders were to endure well over a hundred years of sustained privation, genocidal edicts and ethnic cleansing. Some landlords, like the Macdonnells in Glengarry, were so thorough that the region is desolate to this day. Others, like the Duke of Atholl, press-ganged his men to fight in the American War. When they were done, rather than pay their passage home, he tried to sell them to the East India Company as slaves. They mutinied and once they were reunited with their families, he evicted every one. In 1803, the Rev. James Hall commented, “The state of our Negroes is paradise compared to that of the poorest Highlanders.” He was more right than he knew. There was simply no respite anywhere. Even the church, which might have been a spiritual bulwark, defended its divine right to accept payment for Highlanders sold into outright slavery. Compassion presupposes the existence of a conscience. In 1866, one half of Scotland belonged to 10 people (today, 80 per cent of the land belongs to 0.08 per cent of the population). The landed aristocracy may have called their surgical wilderness of sheep “The Improvements”, but victims of the Clearances were left in little doubt that words can be manipulated. The Clearances were to ultimately relieve the Scottish Highlands of 80-90 per cent of the population and the forest. In the fifty years following Culloden, more than half of the lairds would become absentee landlords. What a consolation it must have been to be hygienically removed from the ambience of all that unlovely suffering — or even better — to discover that one’s compassion is squandered on subhuman barbarian tenants. In the annals of callous indifference, Marie Antoinette will have to settle for a back seat to the Duchess of Sutherland. This painting by her, while technically perfect, is strangely devoid of humanity. The same might be said of her.

At the height of the “Highland Clearances”, it was not uncommon for 2,000 houses to be burned in a single day. Scotland was soon awash in a tide of heartsick, vagrant people. In the way of all disasters, not one thing — but everything — conspired in the ruin: recurrent outbreaks of cholera, widespread tuberculosis, frequent crop failures and food shortages all seemed like minor annoyances when, in the spring of 1846, spores came drifting over the land. The Irish potato blight brought long years of famine. All in all, Highlanders were to endure well over a hundred years of sustained privation, genocidal edicts and ethnic cleansing. Some landlords, like the Macdonnells in Glengarry, were so thorough that the region is desolate to this day. Others, like the Duke of Atholl, press-ganged his men to fight in the American War. When they were done, rather than pay their passage home, he tried to sell them to the East India Company as slaves. They mutinied and once they were reunited with their families, he evicted every one. In 1803, the Rev. James Hall commented, “The state of our Negroes is paradise compared to that of the poorest Highlanders.” He was more right than he knew. There was simply no respite anywhere. Even the church, which might have been a spiritual bulwark, defended its divine right to accept payment for Highlanders sold into outright slavery. Compassion presupposes the existence of a conscience. In 1866, one half of Scotland belonged to 10 people (today, 80 per cent of the land belongs to 0.08 per cent of the population). The landed aristocracy may have called their surgical wilderness of sheep “The Improvements”, but victims of the Clearances were left in little doubt that words can be manipulated. The Clearances were to ultimately relieve the Scottish Highlands of 80-90 per cent of the population and the forest. In the fifty years following Culloden, more than half of the lairds would become absentee landlords. What a consolation it must have been to be hygienically removed from the ambience of all that unlovely suffering — or even better — to discover that one’s compassion is squandered on subhuman barbarian tenants. In the annals of callous indifference, Marie Antoinette will have to settle for a back seat to the Duchess of Sutherland. This painting by her, while technically perfect, is strangely devoid of humanity. The same might be said of her.

Sutherland Born merely Countess of Sutherland, she brought to her marriage an enormous dowry of ancestral lands, while the Duke of Stafford added that much-coveted notch to her title. We tend to think of “philanthropy which chooses its objects as far distant from home as possible” as a relatively recent anomaly. Yet, were she still marring the landscape today, the Duchess would be just the sort of person to fret and agonize over restrictions to democracy and free speech in places like Indonesia and China, while demanding more of it at home — assuming it filled her purse.

Portrait of Elizabeth Leveson-Gower, Duchess-Countess of Sutherland, George Romney, 1782 At the peak of the “Improvements”, the Duchess, then-president of the Stafford House Assembly of Ladies, led the campaign to lecture their “sisters in America upon the subject of Negro-Slavery”. A contemporary scoffed at the enormity of the hypocrisy: The Duchess saw to it that “from 1814 to 1820 … 15,000 inhabitants, about 3,000  families, were systematically expelled and exterminated [from her lands]. All their villages were demolished and burned down, and all their fields converted into pasturage. … In 1821, the 15,000 Gaels had already been superseded by 131,000 sheep.” (Karl Marx, The People’s Paper, No.45, March 12, 1853) Aesthetically offended by her homeless, starving tenants, she confided to a friend: “Scotch people are of happier constitution and do not fatten like the larger breed of animals.” It must have been genetic because in 1899, Booker T. Washington gushed: “We now feel that in the Duchess of Sutherland we have one of our warmest friends.” (Up from Slavery, chapter XVI) Then, during the Crimean War, when recruiting officers came to the Highlands, the men bleated at them like sheep and turned their backs. The Duke of Sutherland was told: “Since you have preferred sheep to men, let sheep defend you.”

families, were systematically expelled and exterminated [from her lands]. All their villages were demolished and burned down, and all their fields converted into pasturage. … In 1821, the 15,000 Gaels had already been superseded by 131,000 sheep.” (Karl Marx, The People’s Paper, No.45, March 12, 1853) Aesthetically offended by her homeless, starving tenants, she confided to a friend: “Scotch people are of happier constitution and do not fatten like the larger breed of animals.” It must have been genetic because in 1899, Booker T. Washington gushed: “We now feel that in the Duchess of Sutherland we have one of our warmest friends.” (Up from Slavery, chapter XVI) Then, during the Crimean War, when recruiting officers came to the Highlands, the men bleated at them like sheep and turned their backs. The Duke of Sutherland was told: “Since you have preferred sheep to men, let sheep defend you.”

There is no greater sorrow on earth than the loss of one’s native land – Euripides

After the sheep came the deer. The Victorians romanticized the Highlands and the nation became a gigantic B rigadoon-type theme park/hunting preserve for the dilettante sons of those who’d starved the crofters. As the Clearances proceeded, the landlords grew only more devious. Some would summon their crofters to meetings, with the threat of exorbitant fines if they failed to appear. Once there, instead of the advertized purpose (dis

rigadoon-type theme park/hunting preserve for the dilettante sons of those who’d starved the crofters. As the Clearances proceeded, the landlords grew only more devious. Some would summon their crofters to meetings, with the threat of exorbitant fines if they failed to appear. Once there, instead of the advertized purpose (dis cussing fair rents), the tenants were bound hand and foot and tossed onto coffin ships bound for North America. Between 1815-38, 22,000 Highlanders were sent to Nova Scotia alone. It should be remembered that for the Highlanders, the Irish (in fact, for most Europeans), emigration meant a complete and utter severance with the Old World. Very few settlers, farmers and homesteaders ever went back “to visit”. Yet, New World terrors of wilderness, health-breaking work, harsh winters, savage animals and misunderstood aboriginal people must have been preferable to the coils of betrayal and starvation waiting at home.

cussing fair rents), the tenants were bound hand and foot and tossed onto coffin ships bound for North America. Between 1815-38, 22,000 Highlanders were sent to Nova Scotia alone. It should be remembered that for the Highlanders, the Irish (in fact, for most Europeans), emigration meant a complete and utter severance with the Old World. Very few settlers, farmers and homesteaders ever went back “to visit”. Yet, New World terrors of wilderness, health-breaking work, harsh winters, savage animals and misunderstood aboriginal people must have been preferable to the coils of betrayal and starvation waiting at home.

According to an eye-witness account: “The people were seized and dragged on board. Men who resisted were felled with truncheons and handcuffed; those who escaped including some who swam ashore from the ship, were chased by the police and press gangs.” Nor did the Highlanders enjoy any of the legal protections afforded African slaves. Ships with a regulated capacity of 490 slaves were routinely transporting 700 Europeans at a go. In the six years between 1847-53, at least 49 emigrants’ ships, each carrying from 600 to 1,000 souls were lost at sea. These “coffin” or “fever” ships, as they were known, were unbelievably putrid vessels. Originally constructed to haul Canada’s timber to Britain, the “passenger trade” arose only when some rapacious genius discovered that human ballast paid better than rocks on the return haul. The voyage took anywhere from one to two months, and three of every 20 passengers would die on board. In 1848 alone, 17,300 Scottish emigrants died either on the coffin ships or in New World quarantine stations. The medical examiner at our own Gross Isle Station in the St. Lawrence River said of the Highlanders: “I never, during my long experience at the station, saw a body of emigrants so destitute of clothing and bedding. Many children of 9 or 10 years old had not a rag to cover them. … One full-grown man passed my inspection with no other garment than a woman’s petticoat.”

Did Robbie Burns save the Scots?

Of course not. It takes rather more than a hundred years of displacement, degradation and trauma to lay the warrior breed low. Gaelic vitality is not so easily eradicated — as the Duke of Sutherland discovered. To their everlasting credit, the Highlanders never did what so many other despairing people have done: consign their humanity to the devil in exchange for a surpassing vindictiveness, outstripping their own oppressors. Perhaps, these others simply failed to produce a Robbie Burns in time to save them from drowning in their venom. “O wad some Power the giftie gie us, To see oursels as ithers see us!” Like most Scots of his day, Burns was certainly no stranger to affliction. His antipathy to the social order was forged as he watched his father’s life ebb away in a vain struggle against crushing debt, poor land, short leases and bad markets. He saw his beloved “Highland Mary” Campbell die a horrible death of typhus just at that splendid peak moment of intoxicated infatuation. Yet, Robbie’s enduring legacy is one of merrymaking, the eternal sport between the sexes and good brawling fun. He still grounds us and reminds us to take pleasure in the little things that make life bearable. Political commentator, nonsense rhymer, writer of love songs, patriot poet; he was all things to all men (and a shocking number of women). He never hesitated to skewer those responsible for Highland suffering, while, in the next breath, he worried himself over the lowly fate of the field mouse. In some sense, he did save the Scots — and all of us. Certainly, he penned that greatest anthem to patriot hearts. And if you’ve heard Bruce’s Address a thousand times, you know that, with every thousand repetitions, it only grows the more powerful:

Of course not. It takes rather more than a hundred years of displacement, degradation and trauma to lay the warrior breed low. Gaelic vitality is not so easily eradicated — as the Duke of Sutherland discovered. To their everlasting credit, the Highlanders never did what so many other despairing people have done: consign their humanity to the devil in exchange for a surpassing vindictiveness, outstripping their own oppressors. Perhaps, these others simply failed to produce a Robbie Burns in time to save them from drowning in their venom. “O wad some Power the giftie gie us, To see oursels as ithers see us!” Like most Scots of his day, Burns was certainly no stranger to affliction. His antipathy to the social order was forged as he watched his father’s life ebb away in a vain struggle against crushing debt, poor land, short leases and bad markets. He saw his beloved “Highland Mary” Campbell die a horrible death of typhus just at that splendid peak moment of intoxicated infatuation. Yet, Robbie’s enduring legacy is one of merrymaking, the eternal sport between the sexes and good brawling fun. He still grounds us and reminds us to take pleasure in the little things that make life bearable. Political commentator, nonsense rhymer, writer of love songs, patriot poet; he was all things to all men (and a shocking number of women). He never hesitated to skewer those responsible for Highland suffering, while, in the next breath, he worried himself over the lowly fate of the field mouse. In some sense, he did save the Scots — and all of us. Certainly, he penned that greatest anthem to patriot hearts. And if you’ve heard Bruce’s Address a thousand times, you know that, with every thousand repetitions, it only grows the more powerful:

Scots, wha hae wi’ Wallace bled,Scots, wham Bruce has aften led,

Welcome to your gory bed,

Or to victorie.

.  Now’s the day, and now’s the hour;

Now’s the day, and now’s the hour;

See the front of battle lour;

See approach proud Edward’s power –

Chains and slaverie!

. Wha will be a traitor’s knave?

Wha can fill a coward’s grave?

Wha’s sae base as be a slave?

Let him turn and flee!

. Wha for Scotland’s King and Law,

Freedom’s sword will strongly draw,

Free-man stand, or free-man fa’?

Let him follow me!

. By oppression’s woes and pains!

By your sons in servile chains!

We will drain our dearest veins,

But they shall be free!

. Lay the proud usurpers low!

Tyrants fall in every foe!

Liberty’s in every blow!

Let us do, or die!

We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation – Voltaire Robbie would approve of his nation of great men who again and again rose from the ashes of subjugation and slavery to create, invent, and reinvent themselves. Cry all you like “oppressed peoples of the earth”, but, as you covet the television, the refrigerator and most of what defines advanced and civil society, try to remember that they are all gifts of a people who have been uniquely persecuted and uniquely able to contribute out of all proportion to their numbers and opportunities. Burns did the same. A true son of Scotland, he rose from obscurity to give much and much that remains as fresh today as it was when first he gladdened Highland hearts.

Fair fa’ your honest sonsie face

As an institution, the Burns dinner varies from place to place, but Robbie would have been the first to condemn dogmatic festivities-by-rote. The rule of thumb ought to be:Could Robbie have possibly enjoyed himself here? The one invariable ingredient of a Burns dinner is the mock heroic address to that “chieftain of the pudding race” — the Well, we’ve tarried too long, and as the old lady said when she saw the grandfather clock fall on the perambulator … ‘Time is on the wain’. Here’s to you, Robbie — now — to the haggis!

As an institution, the Burns dinner varies from place to place, but Robbie would have been the first to condemn dogmatic festivities-by-rote. The rule of thumb ought to be:Could Robbie have possibly enjoyed himself here? The one invariable ingredient of a Burns dinner is the mock heroic address to that “chieftain of the pudding race” — the Well, we’ve tarried too long, and as the old lady said when she saw the grandfather clock fall on the perambulator … ‘Time is on the wain’. Here’s to you, Robbie — now — to the haggis!

LINKS

Burns – poems and “clatter” What did he say? Burns glossary look-up The Clearances The voyage of the Hector This year, say it with haggis

from Carmina Gadelica, Alexander Carmichael

-

- “Our weddings are now quiet and becoming, not the foolish things they were in my young day. In my memory weddings were great events, and singing and dancing and piping and amusements all through the night and generally for two or three nights in succession. There were many sad things done then for those were the days of foolish doings and foolish people. When they came out of the church, the young men would go to throw the stone, or toss the caber or play shinty, or to run races or race the horses on the strand, the young maidens looking on all the while. It is long since we abandoned those foolish ways in Lewis. In my young days there was hardly a house that did not have one, two or three who could play pipe or the fiddle and I hav

- e heard it said that there were those who could play things called harps, but I do not know what those things were. A blessed change came over the place and the people when the good ministers did away with the songs and stories, the music and the dancing, the sports and the games that were perverting the minds and ruining the souls of the people leading them to folly and to stumbling. The good ministers and the good elders went amongst the people and would break and burn their pipes and fiddles. Now we have the blessed Bible preached and explained to us earnestly.” “A famous violin player died in the Isle of Eigg a few years ago. He was known for his old style playing and his old world airs which died with him. A preacher denounced him saying ‘Thou art down there behind the door (of Hell), thou miserable man with grey hair, playing thine old fiddle with the cold hand without, and the devil’s fire within.’ His family had pressed the old man to burn his fiddle and never play again. A pedlar had offered ten shillings for the violin which had been made by a pupil of Stradivarius. The voice of the old man faltered and a tear fell. He was never again seen to smile.” “In Islay I was sent to the parish school to obtain a proper grounding in arithmetic. But the schoolmaster, an alien, denounced Gaelic speech and Gaelic songs. On getting out of school one evening we resumed a Gaelic song we had been singing the previous evening. The schoolmaster heard us and called us back. He punished us until the blood trickled from our fingers, although we were big girls with the dawn of womanhood on us.”

The Duke of Sutherland – today

In 1995, a proposal was made to have the statue of the Duke of Sutherland, which still stands in Sutherland today, removed. The ‘subscriptions’ which paid for this statue were forced out of the destitute crofters on pain of further eviction if they did not comply. The present day local people were totally opposed to the suggestion which had come from “outsiders” not living in Sutherland to remove the statue. These outsiders were in fact the survivors of the families Cleared by the Duke and now settled in America and Canada. The local people have already forgotten what a monster this old Duke was, whereas the people who are now considered to be outsiders remember and acted upon that memory. That is how quickly history can be lost if we are not taught and made aware of our history and culture. Amazingly, the statue carries an inscription that it was erected by his “grateful” tenants”. One can easily imagine why.

Clearances – Today?

In 1993 two farmers on the Isle of Arran were evicted from their family farms to make way for more deer. In the same year, managers on the Wester Ross estate of the absentee landlord Sheik Mohammen bin Rashid al Maktoumm of Dubai bulldozed houses on the estate allegedly because the tenants had been poaching.